Originally Published: August 31, 2016

For as long as I’ve been submitting my work for peer review — both through writers’ forums and as part of creative writing classes — I’ve encountered two main types of helpful critique. One type are people pointing out legitimate problems with the draft. The second type are instances where the critiquer disagrees with the artistic decisions I’ve made and offer alternate possibilities — ones that better align with his tastes. I call the second type helpful not because I want to apply their advice to my next draft, but because their comments have helped me form a firmer conception of what my writing style is.

Style is a more advanced topic than what this blog normally covers, but knowing what you want to do and where you want to go with your writing is extremely helpful when dealing with and sorting through criticism. Staying true to those goals will not only bring you satisfaction as a writer, but also a genuine audience for your work.

Emotion and Negative Space

A particularly relevant and memorable case study was a short story I submitted to a writers’ forum in January 2016. One of the main critiques that I received was that my main character Steven seemed inappropriately nonchalant, given the situation he was in. Initially, I lumped all of these critiques into the first type. Steven’s portrayal was a symptom of the story’s deeper issues — ones I plan to address when I revisit this piece and give it the longer treatment it deserves. Yet as I read the critiques more closely, I was surprised how many my muse was outright rejecting, how many proposed fixes did not fit my vision. It didn’t take me long to see the pattern in all of these rejected proposals and follow it to one of the core features of my writing style.

Emotion isn’t something I want to dwell on. I prefer that it remain largely implied, rather than stated outright. One reason why this is so is because there are people in my life who tend to externalize their emotions. I’ve seen them explode and fling their bad moods at other people. I’ve seen them pull others into their anxiety spirals. They must express their feelings. They don’t like it when someone refuses to listen to them or reacts in a way they don’t consider appropriate.

To be fair, I admit that I’m more sensitive to the emotional temperature of a room than most. Due to some fluke of psychology, the stronger the ambient emotions are, the stronger my urge to flee. I also have the bad habit of picking up others’ emotions just so I can stay under their radar. But I can’t deny that what these people are doing is emotional manipulation — whether they’re aware of it or not.

Hopefully, now you can see why I’m so hesitant to deal with and express emotions directly. It’s because I have witnessed and experienced the harm such behavior can inflict when it’s taken to extremes. Call it cowardice, a coping mechanism, or compassion, but I leave others’ emotions alone, both in fiction and in real life. There are other reasons why I don’t like stating a character’s emotions in narration, but that is one.

Image Credits: Ataturk.svg: NevitNevit Dilmen, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

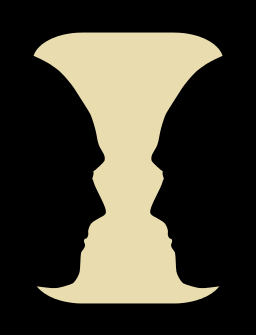

My high school theater teacher always said, “Ninety percent of acting is reacting.” The lesson I took away from her class is that what you don’t say is sometimes more important than what you do say. I correlate this with the concept of negative space from the visual arts. (For those of you who aren’t familiar with the term, this is the space that is deliberately left empty, as opposed to positive space — space which is filled in by something.) But long before I had a name for it, this concept fascinated me.

In third grade, I was given a reading comprehension assignment for the novel we were reading in class. One of the questions urged us to “read between the lines.” I took this phrase literally and focused on the space between the lines of printed text, thinking that maybe the fibers of the paper would form words and those would be the answers I was looking for. Once the phrase was explained to me and I was told what I should be paying attention to — what the characters are not saying and what they are not doing — I was surprised to find this whole other dimension to the story. It was a jump between 2D and 3D, and it was awesome! So I started paying attention to this third dimension in every story I encountered. This encouraged me to actively read and watch, and as a result, I could enjoy these stories far more deeply than before.

When I began writing my own stories, I immediately started playing with negative space. How much can I say without saying it? In a way, it’s an experiment on how much the audience is willing to pay attention, how much thought they are willing to invest, and how this differs from reader to reader. And given my natural hesitation to address emotion head-on, the emotions of my characters frequently reside in that negative space.

The reason why my muse rejected so many critiques of my 2016 short story is because my critiquers were encouraging me to say what Steven was feeling. I didn’t want to say these things. Instead, I wanted to sculpt the negative space to show that Steven was sad, angry, or frustrated. The feedback showed me that I had failed in this attempt, that I need to give the reader more time with Steven and better define the borders of that negative space.

Functional Language

People who have read my work have consistently commented on my use of what they call “functional language.” I usually define it as clean and simple. Many have praised this, calling it a stand-out feature of my stories. Others have been more negative, including one who observed that I “passed up opportunities to be more expressive.” This mixed feedback highlights a difference in taste, which is why I’ve included “functional language” as part of my style.

I want my words to be understood rather than admired. I don’t want people to come up to me in the future saying that they love how I use the English language — that it’s so pretty or so unique. I don’t write to be pretty. I write to tell a story. The words I put on the page are there to serve that greater purpose. Nothing more.

As a child, I was diagnosed with what they called a “speech disfluency.” Stuttering is the more common name for it. This will surprise people who have met me in real life. The fact that you can’t tell is because my acting training is paying off. Though trust me, as tremendous an asset that training has been, it can still fail at the worst moments, giving that old “disfluency” beast the opportunity to haunt me again.

When I was a girl, it was hard enough just to speak words. To communicate verbally and actually be understood was a true, physical battle. Thus, the desire to be understood set in deep — deeper than it does with others for whom talking comes easy. It’s a big reason why I turned to writing as a teenager, and why I’ve always preferred function over aesthetics in word choice.

This is also the reason why I’ve never liked the phrase “painting with words.” In my mind, language is not meant to be pretty. Language is meant to communicate something, to pass ideas from one person to another. If nobody understands what you’re saying, then who cares how pretty your words are? It’s still meaningless.

This doesn’t mean that I hate beautiful language, or that I don’t use figurative language — metaphors, similes, etc. Far from it. Writing is an art, and all art strives to be beautiful. I do use figurative language. I like a well-constructed, interesting, and thematically relevant metaphor, just like any other writer. But I believe that beautiful and figurative language should enhance what you are trying to say, rather than obfuscate it. Confused readers are disengaged readers.

The thing with beauty is that it’s in the eye of the beholder. Not everyone enjoys searching the areas of negative space for additional meaning. Not everyone will appreciate language that doesn’t try to impress in a creative work. But that’s okay. Because I’ve found people who like my style the way it is, and who are just as excited about my story’s future as I am. This is the kind of audience I’ve always wanted to find.

I hope this exploration of my style, and how life has shaped me as an artist, will guide you on similar journeys. If you are just starting out, you may not see it right now. But once you’ve built up a good-sized body of work (I’d guess at least a dozen different stories), even if they’re still drafts that you haven’t shared with anyone else, then it will emerge.

What is your writing style? What are your writing goals? Everyone has their philosophy on art and what it should be. Your views are likely very different from mine. Feel free to share your musings or manifestos in the comments below. But please, let’s be civil, okay?