Ms. Caldwell, are you seriously advising people to write scripts? Scripts are for movies. You’re not writing a movie. You’re writing a story.

Prosecutor, you do know that storytelling isn’t limited to one…

Fiction! You’re writing fiction! Prose! Prose is not a script. You’ll never capture the essence of prose in a script. You’ll never strike at the heart of fiction. Or perhaps you’re deliberately avoiding it since your generation’s minds are so rotten you can only appreciate movies and anything that imitates them.

Ad hominem against an entire generation. Wow.

So will the defense admit that she and this Peter Rock fellow she’s been quoting for the past several posts are both frauds and leave fiction to the true literary artisans?

I admit that the prosecution is making a lot of assumptions.

Correct assumptions.

No. Just understandable ones.

Wait. Are you refuting me? Do you actually have a counter argument?

I am, and I do.

Ladies and gentlemen of the jury, I trust you are already familiar with Exhibits A and B. Now, I wish to present Exhibit C — a stage adaptation of Exhibit A. This is the final piece of evidence I need to refute the prosecution’s assumptions. How? Allow me to explain.

The Inherent Incompleteness of Scripts

My first love will always be creative writing, but my second love is theater. That’s why Exhibit C is a stage play and not a screenplay. I’m more familiar with the medium of theater than the medium of film.

I learned a lot from Professor Todd’s History of Theater classes in college. Yet the most relevant thing I learned is this:

“A play is not complete until it is performed.”

Scripts are never the final product in and of themselves. They are merely guiding documents that aid in the creation of that final product. Consequently, script writers must make their peace with the fact that they are creating an inherently incomplete work.

The reason why scripts are synonymous with theater and film is that these are collaborative mediums. It takes a team of people to put on a play or make a movie. You need a singular vision and a shared reference document to coordinate everyone’s efforts. Often, it’s the writer who creates the shared reference document and the story contained within it. It’s the director who interprets said reference document, develops that singular vision, and leads the team in realizing it.

As a result, script writers must always write with that final product in mind — the movie that is filmed or the play that is performed live. Thus, the script writer must keep the limitations of the final medium in mind as well.

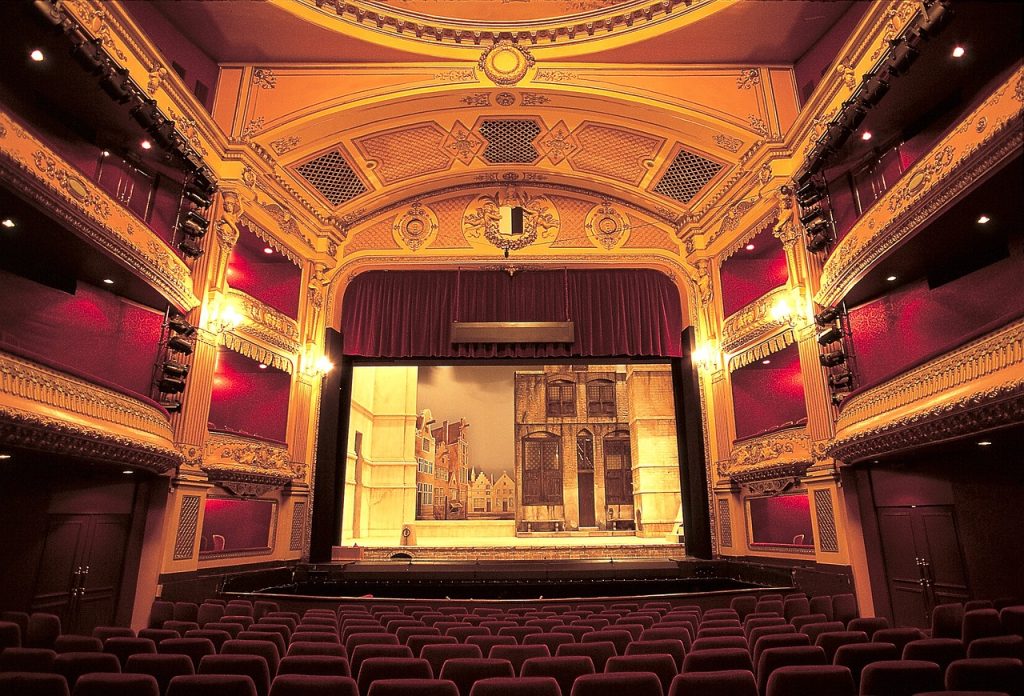

The Restrictions of Theater

When it comes to live theater, there are plenty of restrictions you need to work inside. Two big ones are the capabilities of human actors and the dimensions of the stage they’ll be performing on. You’re also restricted to physical costumes, a physical set, physical props, and practical effects. Modern technology and machinery have done much to expand a theater company’s toolbox, but not every venue has all of this equipment. And none of them cancel out the fact that every aspect of a theater performance must be concrete. There’s very little that you can reliably and effectively abstract away without losing your audience.

Adapting “To the Capital” for the Stage

At different points in my amateur theater career, I’ve been both a director and an actor. In either role, I like scripts that are specific with the core details but leave enough room around them for my interpretation, be it a directorial vision or my portrayal of a character. When I decided to adapt “To the Capital” into a stage play as a companion piece to this post, I naturally kept an eye on what my inner director and actress would like to see in the script. Thus, a significant part of my job as playwright was stripping this scene back to its essential elements.

In stage plays, you’ll usually find most of the establishing information at the beginning of the scene: location, time of day, as well as how the scene looks at the beginning and how characters are situated within it. This is a helpful convention for the stagehands. Everything they need to know is easy to find, and they aren’t required to read the whole script as closely as the cast and director do. That’s why description is so front-loaded in Exhibit C instead of being more spread out in Exhibits A and B.

Kiki

The character of Kiki ended up being the catalyst for many of the differences between Exhibits B and C. Makeup and costume can do a lot to give Kiki’s actress a fairy appearance: fake wings, fake pointed ears, glitter on her face and clothes. But since she and Silas must be portrayed by human actors, they will always be of comparable size. The vast size difference I described in Exhibit A simply isn’t feasible. Thus, I changed Kiki’s initial placement and what she does at the end to account for this.

Night. Train ambiance. SILAS sits on the bed stage left, his eyes closed. KIKI sits in front of the bedside table, restless. A lit lantern rests on the table. Blankets lie in a pile downstage right.

This opening stage direction echoes the first paragraph of Exhibit A, though way, way truncated. The lantern is still there in the same it is in the prose version. The biggest change I had to make was moving Kiki off the table and onto the floor in front of it. The blankets are a hint about what happens at the end.

KIKI voices her frustration. She then lies down on the pile of blankets, covering herself with one before falling asleep.

Kiki is too big to sleep in Silas’ coat pocket now. But the story demands that she have a place to sleep too. So, I added the pile of blankets for her in the play’s final stage direction.

There is No Telling in Theater

Theater and film are mediums that are 99% show. You can’t easily or cleanly tell anything in a play or movie. Sure, plays have soliloquies, but those are inherently fourth-wall-breaking. They highlight the artificiality of a play by addressing the audience — making them self-conscious again. You can have a faceless narrator who exists outside of the story in film (unlike a play), but their parts will only ever be interruptions, not an integral part of the story’s flow.

Since the medium of theater limited me to what Silas and Kiki say out loud, my stage adaptation had to omit all of the facts that the narration provided in the original prose. Raj, his illness, and the friendship between him and Silas. The prejudice against Lijani. Silas’ golden eyes marking him as Lijani. That Silas used to live in the capital but was forced to leave years ago. For Exhibit C to fully convey everything I managed to in Exhibit A, I’d need multiple scenes.

Could I have written Exhibit A to be multiple scenes instead of only the one that’s currently written? Absolutely. But none of what I’ve mentioned was my inspiration — what motivated me to write this piece in the first place. It was all backstory and context for this conversation between Silas and Kiki — the part I actually wanted to write. I know I didn’t need to demonstrate (aka show) all of that in order to create the final product I envisioned. I trusted that my readers could fill in the blanks based on what I told them about what happened in the past. The medium of fiction afforded me that opportunity.

The medium of theater did not grant me the same opportunity with Exhibit C. The medium’s restrictions would have forced me to go beyond my inspiration’s scope and write more scenes than I was motivated to. While I strove to make an adaptation that could be performed, that wasn’t the piece’s primary purpose. I created Exhibit C, first and foremost, for the purposes of comparison and argument, not performance. Thus, I knew that writing these extra scenes needed to convey the full story would be unnecessary effort. The stage play could serve its primary purposes just fine without them.

Conclusions

My thesis, Your Honor, is that the script format isn’t what influences the writer’s mindset. Rather, it’s the writer’s mindset that influences what’s included in the script. Once you let go of your preconceptions and examine what a script truly is, this becomes clearer.

Scripts are not a medium unto themselves. They are simply one format a planning and reference document can take to aid in the creation of art in multiple mediums.

The written stage play is not the play that is performed, yet it is written with that performance in mind. That’s how a playwright captures “the essence of theater” in their script, with all of the restrictions and freedoms that medium affords.

In the same way, a planning script like Exhibit B is not a piece of fiction like Exhibit A. Yet a planning script is written with the final piece of fiction in mind — the one the reader ultimately reads — along with all of the restrictions and freedoms the medium of fiction entails.

So yes, Your Honor, a script can capture “the essence of fiction” when a script is written with fiction as the intended final product. The writer just needs to bring the appropriate mindset to the task and be clever enough to use it.

So, members of the jury, what is your verdict? Have I persuaded you? Or are there still holes in my case? Please share in the comments.

One response to “Scripts, Theater, Fiction, and the Essence of Medium”

[…] This is a companion piece for my post “Scripts, Theater, Fiction, and the Essence of Medium.” […]