In a previous post, I mentioned message as one of the essential ingredients for a story. I think it’s high time that I discuss what I mean by this.

You said that message is a lot like theme.

Yes, I did, astute reader. It’s not the same thing but it’s similar.

But hold on. What’s theme?

Well… there is no one definition that everyone agrees on. Here is the best one I could find:

Properly speaking, the theme of a work is not its subject but rather its central idea, which may be stated directly or indirectly. For example, the theme of Othello is jealousy.

The Penguin Dictionary of Literary Terms and Literary Theory, 4th ed.

That’s not what I was taught.

Same here. Some of my teachers said that main/central idea was a separate thing. Many said that a theme can’t be a single word. For the latest insight on what English teachers are saying today, I asked my little sister what she learned in class this past school year. She dug through her notes and found four different, at times contradictory, definitions — all from the same teacher. No wonder she struggled with this concept.

However, I have noticed one thread of consistency running through all of these definitions. They all imply a grand, abstract statement about the examined piece. “Love defies death”, “jealousy leads to ruin”, and “sacrifice brings redemption” are often-cited examples of theme. These are all well and good in English class and when writing a literary analysis paper. But from a writer’s perspective, these are intimidating.

Here’s the blunt truth, folks. Comparing your story about a jealous ex to Othello is absurd. You have no business comparing yourself to Shakespeare. That is a job for your readers. It’s your readers who will decide who to compare you to and whether you deserve it. If they do, good on them. You don’t need to give a damn, and I advise that you shouldn’t.

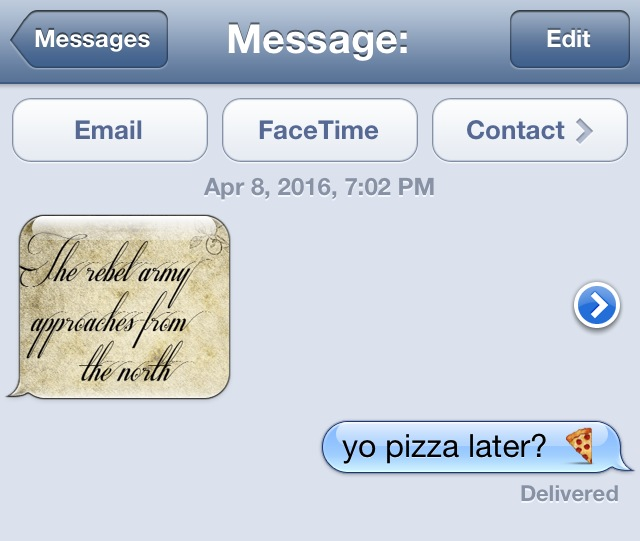

I bet that mini-rant has confused you. I don’t believe that the concept of theme is useless for writers. Far from it. I just don’t like using that term. I much prefer the term “message” when talking about this. Why? First, it’s much broader in connotation, thus less intimidating for a writer’s use. “The rebel army approaches from the north!” and “yo pizza later?” are both messages. Second, message has a universally agreed-on, common sense definition that all English speakers, regardless of education, can grasp.

Message answers the question of why this story is being told. We can use it as a compass to inform character motivation, the direction the plot moves in, and ultimately, the story’s ending.

Let’s say I’m writing a story where my protagonist is on a quest — standard fare for fantasy. The protagonist emerged out of pre-writing as an extremely loyal person. This intrigued me, so I decided to write about this character’s loyalty. When developing the plot sketch, I laid down anchor scenes which identify who he is loyal to, why he is so loyal to them, and finally how he ultimately proves his loyalty in completing the quest. As I fill in the rest of the plot, I can insert tests of his loyalty and dedication to the quest either by making the journey difficult or tempting him to abandon it entirely in exchange for some form of immediate gratification.

My advice is that you don’t worry about message when your story is fresh and brand new, when you’re just starting out with this idea. Let it settle down and solidify first. For fellow planners, wait until you’re ready to start nailing down the details in your framework — be it a formal outline or something more free-form like a plot sketch. For those who prefer to write by the seat of their pants, identify your message after you’ve finished the first draft and before you begin the first round of revisions. Doing it this way can help you focus your efforts and avoid making so many revisions in the long run — aka you can polish it up faster.

But what form should your message take? Some teachers create formulas for constructing it and rules for what the elements should be. All you really need is one sentence or phrase that makes sense to you. Specificity is generally better than vagueness.

So, am I right about theme? Do you disagree with my preference for “message”? Did I totally miss the mark? Or are you still confused? Leave a comment below.