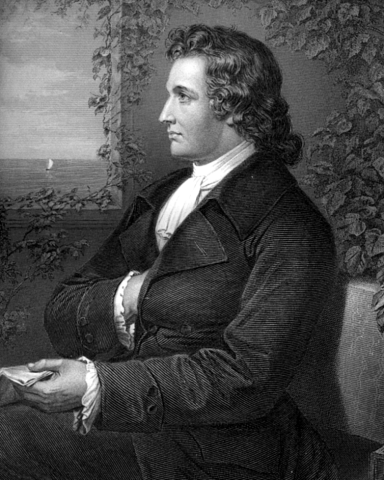

If I learned nothing else from Professor Todd’s classes, it was Goethe’s Three Criteria. Though Johann Wolfgang von Goethe is best known as a poet and playwright, he also wrote criticism and is credited with developing a three-part critical framework. Professor Todd drilled these into our heads in his History of Theater classes. The written assignments we had to complete after reading each play had questions that were derived from these three criteria.

The beautiful thing is that these criteria can be applied to any artistic medium. It’s a method of criticism that has influenced how I critique fiction. Last time, I discussed whether critiques can (or should) be objective or subjective. If you look closely at Goethe’s Criteria, none of them can be evaluated from a purely objective standpoint.

1.) What was the artist/writer/creator/etc. trying to do?

What message is he trying to convey? This sounds pretty straightforward, right? Yet a critic’s opinion of this can be different from the author’s intentions. When the author is intentionally vague or ambiguous, then it becomes a field day for critics and ordinary readers. Multiple theories and interpretations of the author’s message are formed as a result. For instance, are the ghosts in The Turn of the Screw real or not? Henry James’ story is ambiguous, thus literary scholars have been debating this for years.

2.) How well does the artist do it?

Did she succeed at the goal examined under question one? Did she convey the message she intended to? Well, define success. Can ambiguity be considered successful if it’s intentional? If a reader doesn’t understand the message, whose fault is it — the reader or the writer? Most would likely blame the writer. But readers can miss things. What if the reader misinterpreted the writer’s message from the beginning? The answers may not be as simple as we believe.

3.) Was it worth doing?

Is the story worth telling? This question is completely subjective since the answer largely depends on whether the reader enjoyed it to some degree. At least, the reader needs to feel like her time wasn’t wasted with pointless crap. A piece can be informative without being enjoyable in the conventional sense. A large part of nonfiction falls into this. But maybe you disagree.

In my critiques, I try to avoid answering the final question. If I liked the piece, I’ll definitely say so. If I didn’t like the piece, I’ll admit it. But I don’t think it’s polite or helpful to call someone’s story worthless in a critique. A story that isn’t published can change and become worthy of its audience. Writing isn’t an all or nothing game.

Have you heard of Goethe’s Three Criteria before? How do you approach critiquing? Let me know down in the comments.